Even though Telefunken made legendary pro tape decks like the M15-series and the M20,

one would not immediately think of the company as a purveyor of

cassette decks. And yet, here is the RC300, the top model in the 1982

range, with two reasons for distinction: it had TFK's own High Com noise

reduction system (seemingly at the exclusion of Dolby B, but read on

...), and it was built around the mighty Papst

Multidrive. Papst already was deeply embedded in quality audio systems,

providing motors for Studer-Revox and other tape machines, as well as

for high-end turntables (Michell Engineering, Audio Note,

Wilson-Benesch, ...), even direct-drive modules for Dual. But the

Multidrive was a bit of a unique thing in the catalogue: a complete

cassette mechanism based on a single cast metal block, containing three

brushed direct-drive motors and one or two capstan flywheels. (How many all-direct-drive

cassette decks do you know?) The headgate was raised by means of a

twin-coil solenoid of serious proportions, resting between the two reel

hub motors, and lowered by a spring. It won't get any simpler than this

(simpler, not cheaper!), and people dreaming of the emergence of a

21st century quality tape drive would do well taking note of this

elegant and realisable architecture (then again, read on ...).

Multidrive was employed mainly by ASC and in this one Telefunken. It was also to be used in Dual's forthcoming C842RC flagship, until that company's financial problems put paid to that, resulting in the Japan-sourced C844 instead (followed with the fine Sankyo-based C846 and CC1462).

So here we are: Telefunken RC300, fully direct-drive, direct loading of the cassette, High Com, two heads, and ... two speeds. Yes, like the Nakamichi 680: 4.76 cm/s as well as 2.38 cm/s!

RC300s are not particularly rare in Germany, and reacting to a permanent query on kleinanziegen.de I could count myself lucky in scoring one for a reasonable price, stated to be defective, hoping for an easy fix and certainly not knowing that this was going to be my longest restoration to date, december 2024 to october 2025!

Despite minimal packing the deck arrived unscathed. After an internal inspection I took my chances in powering it up. Some LEDs came on, others remained dead, but (hurrah!) the level meters flashed all of their segments (dead segments are a usual and irrepairable issue with this model), no smoke escaped, no funny noises were heard. As expected the mechanism itself remained lifeless.

The main cause was quickly found to be a blown fuse in the +15V supply, which was no cause for joy: why did it blow? The mechanism was disassembled and inspected, then lubricated. After putting it back together the tacho disk rubbed against the motor coil PCB. Luckily the backside capstan bearing can be adjusted, pushing the rotor towards the user, away from the coil. This was successful insofar the deck now ran, albeit at lowish speed and with high wow&flutter.

This is an old machine, with quite a few proprietary components. Pre-dating the 230V era it seemed wise to add some protection for over-voltage. First all AC-facing capacitors had their voltage rating increased. I added a 150R 7W resistor in series with the mains inlet (there is a very convenient place for this, but don't do so if you are not formally qualified!). The LED level meters are a monolythic unit. Individual LEDs often fail, in which case no replacement is possible. By some stroke of mine were still fine. I protected the meters by inserting a diode in their supply lines, reducing local power dissipation. Finally the cassette well bulb was replaced with two green LEDs in series, fed through a suitable resistor.

At this stage I was confident enough to operate the deck for longer periods of time.

This quickly brought a new problem: during play the head gate dropped down, while the reel motor kept pulling. A long analysis of the circuits, taking measurements, ultimately concluded something was wrong in the solenoid current source, a circuit including a string of diodes, one of them inexplicably being a signal diode instead of the others (N4001s). This got replaced with a power diode.

Back to testing ... Initially speed and wow&flutter were OK. To gain long-term insight I usually log a few speed runs in WGFUI. Some of these now at times showed a steady drop in speed over several minutes, followed with a sudden return to normal. Still later sessions had less of this jerky behaviour, but exhibited increasingly more wow&flutter. Probing around in the motor controller circuit revealed voltages chaotically jumping over many volts where slowly-changing DC is expected. The bottom side of the motor (diode D705 and T716) showed a periodic voltage remnant at ~30Hz, with 85% of the duty cycle seemingly normal, and 15% pure noise. This stymied me for a while, but these noise bursts ultimately gave a hint: it was as if the commutator only worked properly for 85% of each rotation, or 6/7th. The commutator has 7 sections.

Opened the transport again, and lo, the capstan motor commutator and brushes were covered in a thin layer of black goo. My theory: the initial rubbing of the tacho released rubber-like debris in the cavity, which was caught by the commutator's lubricant, soiling the commutator and the brushes, leading to increased and inconsistent contact resistance.

All motors were properly cleaned, again, now with any lubrication left out, after which all went back to normal. By the way, at this stage it was clear that the three motors' tiny and thin brushes as well as the fragile tacho magnet disc must be the weakest points of the mechanism: prone to wear, and irreplaceable.

In an attempt to debug the erratic speed controller I constructed a breakout cable for the motor, allowing me to operate it on an external power supply, while still keeping the tacho connected to the RC300's circuits. Connecting the scope to the amplified tacho signal and to the controller's output, I could observe proceedings. The raw motor appeared to have poor speed stability, +/-15% , admittedly seen in unloaded mode. The speed controller, then, showed frequent downward glitches on its output, exceeding -5V. Clearly, the control loop bandwidth was ludicrously wide, and its power supply rejection disappointingly low. There were also 100Hz disturbances, originating in the raw 34V supply used for kick-starting the head bridge solenoid.

The motor controller design is overly complex, using something akin to diode logic for implementing a zillion operating modes, each with its own reel braking and tensioning regimes. It results in a supremely smooth ride, but makes debugging hell. I gave up ... Really: I gave up.

Then my long-standing internet search unearthed another RC300 in Germany, this time with electronics problems, but, as the owner testified, "it runs normally". Outwardly dirty and scratched it eventually proved better than expected, but with one segment of the counter out of order, and one channel playing 20dB low. The mechanism and head seemed healthy. I labelled this machine '2', the other one obviously being '1'. After bringing '2' into the same state as '1' it kept blowing its main fuse whenever a cassette played for longer than 20 minutes or so. This took a while to diagnose, along with a bag of fresh fuses, but one time I was lucky enough to witness one blow, smoke rising from the fuse holder, and not the fuse itself. Thoroughly cleaning the holder's contacts put this issue to rest.

My plan was to use '2' for debugging '1', then fixing both and selling one. Surely making '1' go again with a perfectly-operating '2' literally next to it, connected to the same measuring equipment, would be a doddle, not?

Not. The speed controller remained a total mystery, both machines behaving like different species, and no clue as to any defective component in '1'.

So I started mixing up parts. Mechanism '2' in deck '1' worked nicely... for a couple of hours. Then it went erratic, too. Mechanism '1' in deck '2' also was no success. I admitted defeat, abandoned deck '1' altogether, transplanting its counter display, one High Com module, and the pristine face plate to deck '2'. This provided me with a fully-functional machine, now with decent speed stability.

I suspect that deck '1' has issues both in the mechanism and in the speed controller. Of the latter I have no idea at all (else I would fix it). As for the mechanism ... brush wear, combined with superficial damage to the tacho disk?

The electrical design is idiosynchratic like none I've ever seen.

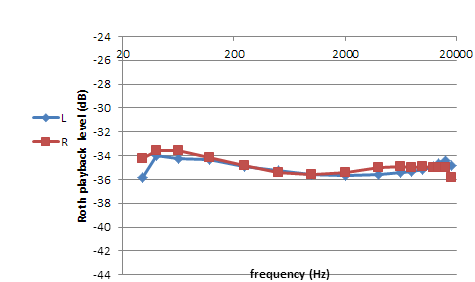

Type I playback uses 100us equalisation, where one would expect significantly higher than 120us for the Alps sendust head (only heads with very small losses operate well with the 'standard' 120us time constant). This is reflected in a severely depressed high midrange and treble region when reproducing the Hanspeter Roth 30Hz-18kHz playback response tape. (Incidentally deck 1 and deck 2 gave the same result.)

Recording Type III, FeCr, is supported, but contrary to IEC III requirements uses 120us playback equalisation. The master record sensitivity is set for type II, with fixed ratio attenuations for type IV and then for I and III combined. Type II recording the loudest by design suggests that this deck was made strictly with chromium dioxide in mind and not for the, at that time more sensitive, ferro-cobalt types. The record amplifier/equaliser is complex, but eq is not switched between the four types. Apart from a very necessary switched treble boost for half speed, there is only a small filling in of the mid-treble for type III, compensating FeCr's typical depression in that area. You read it well: the RC300 treats all tape types essentially the same in recording! Doubting my eyes I looked into the Japan-built RC200's diagrams and found the same remarkable philosophy.

Combined with the aforementioned treble rolloff in playback this results in a cassette deck that totally neglects all aspects of IEC standardisation and inter-operability.

Bias is 85kHz: low for a deck claiming 20kHz record/playback capability. There are no real bias traps, only a first order cut-off at 20kHz looking from the head into the record amplifier. The meters go only to 2dB over Dolby level, forcing the user to keep record levels down (and HighCom on). The meters are equalised, though, showing the output of the record amplifier, including record eq treble boost. (Strangely the RC200 goes to +6dB, but I am not convinced it has a better head.)

As I planned on keeping this deck at least for a while it had to be made compatible with modern-day recording, and that means capable of playing back tapes made on my Nakamichis, and recording with acceptable quality.

The first hurdle is of course that debilitating playback treble loss due to the designers' cheating with 100us, thus inflating the SNR figure in the leaflet. Assuming that the Alps sendust head is not too dissimilar from the Canon sendust type used in all (but one) 2-head Nakamichis since the BX-1 I focused on reworking the PB eq to 150us. In fact, I used the PB amplifier response of the CR-1 as a template, increasing both the time constant and the treble peaking of the Telefunken until the latter's circuit response almost matched the Nak's. (The picture below shows a modified left channel response next to the original right channel.)

With the entire treble area thus raised this resulted of course in treble-heavy and unbalanced rec/play curves: the inverse correction curve had to be applied to the record equalisers. A -3dB treble shelf was added to the record gain alignment circuit, and the latter was reworked to offer maximum gain with metal tape. This required that the control signal for transistor T1308 was moved from Metal to CrO2. The resistor values were adapted to provide a reasonable sensitivity match for Sony Metal XR 1989 or 1995 (also many Maxell MX), Maxell SXII 1991 (close to SA and IEC II reference U564W), Maxell UR 1994. Ultimately I made the alignment around SXII.

The type III record equalisation network was defeated, and its bias trimmer expanded to allow less bias. Thus the FeCr position was converted into an extra type I selection, intended to be set to a higher bias for tapes like Maxell UDI-CD.

Even so the final recording performance was not to write home about. Maxell SXII gave quite flat rec/play curves extending to 19kHz at -20dB and 10kHz at 0dB, yes, but MOL was a paltry 1.5dB above Dolby level. UR managed +3.2dB, and UDI-CD in its special slot even +5dB, but the responses were channel-imbalanced and with a significant plateau in the high midrange and low treble. Metal type showing an opposite channel imbalance I did not even bother with it. After all who would use a deck with low MOL and inadequate metering to record onto metal tape?

(As usual for two-headers: most sweeps started at 200Hz for easier synchronisation in audioTester.)

In a way a pitty, because Telefunken's reasoning was that for the low-speed mode type IV would be used. That now being impossible I reverted to SXII to test this deck's mettle when hamstrung. This gave a frequency response out to 11.5kHz at -20dB and 5kHz at 0dB. Not that one would want to record that high, because MOL had dropped to -1.5dB! Then again, Telefunken's continuing reasoning went that HighCom be used, of course.

Part of the mediocre headroom of this deck has its cause in the record and playback electronics. As mentioned before, these are overly complex due to the need to switch equaliser segments for four tape tapes, two speeds, and cue/review in and out of circuit. This is done with standard BJTs as opposed to more specialised devices, resulting in a great deal of even order distortion, on top of the head/tape-caused odd order distortion. Maybe the deck can be improved somewhat by removing all unwanted functionality, and replacing the remaining switches with something more suitable. But I won't go there...

Telefunken gambled heavily on High Com, but as totally neglecting Dolby B would be commercial suicide early HC-equipped decks sported a 'D NR Expander' button (the 'D' styled as in the Dolby logo), said to offer Dolby-compatible playback decoding. It was quickly found that with the addition of some signal switching the High Com circuit could be made into a Dolby-like encoder, and this functionality was added to later Telefunken decks, including the RC300. This was not exactly advertised, except for a dry "In der Schalterstellung D NR Expander koennen auch Aufnahmen gemacht werden". To show that this was for real I recorded white noise at four levels with "D NR" on, and replayed them with "D NR" off, while graphing the responses:

Playback of tapes recorded on my CR-7 or CR-4, no noise reduction, is quite good, with decent space and detail. Tonally the bass is a bit odd. Commercial prerecordeds fare less well: with D NR enabled they are dull, and with pumping effects.

Record/play performance at both speeds, on Maxell SXII, with an without High Com you can assess yourself with this MP3 download

Keep in mind that this deck, with its modified equalisers, can no longer be regarded as representative for what Telefunken intended. I hope to bring deck '1' in a fully working and original state (except for the horrific speed stability) to find out how that one sounds.

_speed_wf.png)

_speed_wf.png)

_hpr_pb_response.png)

_Roth_pb_fixed.png)