Cassette mechanisms are a specialty component. It is not surprising that in the late 1970s the large consumer electronics manufacturers started outsourcing their mechanisms from expert OEMs that themselves remained in the shadows.

In 1981 Onkyo's new top-of-the-line deck TA-2070 debuted with a double-capstan brushless direct-drive transport made by Sankyo Seiki. This transport and its later derivatives would garner some fame: by 1982 it got picked up by none other than Nakamichi, replacing the legendary 'classic' Nak mechanism. Today the Sankyos are known as high-quality, not without flaws and problems, but generally easily and reliably to repair and maintain.

I always wondered what came before the TA-2070, before 1981? Surely the Sankyo mechanism did not emerge perfectly-formed onto the scene, and must have had an ancestor? Something to bridge between the relatively crude transport of Sankyo's own late 70s STD-3000 three-headed deck and the (seemingly) svelte TA-2070.

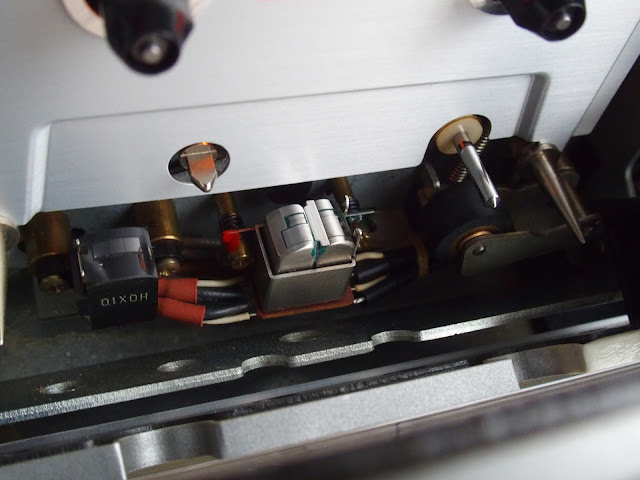

Earlier Onkyo's top position was taken by the TA-2080, a typical late-seventies mega-deck: bulky, complex, proprietary. Then 1980 saw the arrival of the sexy two-head TA-2050, and somewhat later the three-head TA-2060, both with the same single-capstan direct-drive mechanism. A mechanism almost as simple as possible: the direct-drive capstan motor, a reel motor with idler connection to the hubs, a single large solenoid for raising the head bridge via a yoke. Reel braking is done via electromagnetical brakes in both hubs, the supply-side brake also being used to generate back tension. This mechanism abolished a great deal of mechanical parts in favour of electronic control. This should have been a huge success (read on), but only a few Onkyos used this particular configuration before it disappeared again. (The other early adopters, 1981's Sansui D-350M and D-550M, reverted to belt-generated back tension and mechanical brakes actuated by a second solenoid. Later Sankyo mechanisms followed this scheme, ultimately replacing the control solenoids with the cam motor that by now is infamous for its dead-spot problems.)

The only extra in the TA-2060 is a belt connection from the supply hub to a rotating magnet and Hall sensor. These are used as a motion detector, and not for back tension as the picture may lead you to believe. This detector controls the autostop regime, and also provides speed feedback to the back tension regulator sitting on a circuit board behind the mechanism.

The direct drive motor is a brushed type of large dimensions, hidden in a rubber sock for vibration and noise control. In use it emits a faint hum. This motor can be taken apart for servicing relatively easily.

Transport maintenance

After the reconstruction of my mechanism it got plagued with violent speed instabilities. This was caused by an intermittent short between the motor control PCB and the bottom-left post of the mechanism. I painted the top of that post red (you can see it in above picture) for improved isolation.

Reel drive is via the usual rubber idler wheel. I replaced it with a slightly-sanded o-ring of similar dimensions.

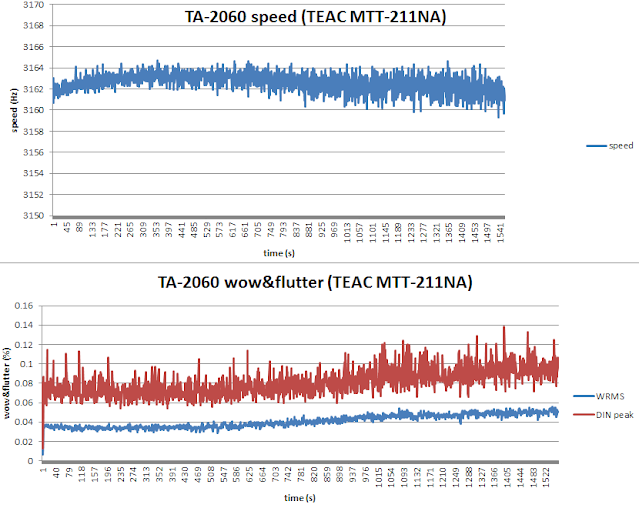

After servicing wow& flutter initially looked very promising, being low both at the beginning and the end of the tape. It was a major disappointment then when a full 45 minute run (see above, blue curve) saw W&F grow chaotically towards the end, with an unacceptable performance in the second half of the tape.

From my first quick trials I knew that W&F quickly measured at the

end of the tape was pretty good, so something strange was going on. I let the deck rest for a few

hours, and then made a second run with the same cassette, now starting

half-way the tape. And see, wow& flutter was significantly lower

(orange curve)!

Spectral analysis of the raw signal of the speed tape showed a dramatic broadening of the signal peak with progressing time, indicating severe drift and very low-frequency wow (blue: start of tape; pink: end of tape). Music would probably be unlistenable!

After more experiments (not that many: there is only so much one can try with such a simple mechanism) I concluded that back tension got instable with time, possibly the electromechanical brake warming up?

Despondently I walked away from this problem and finished the rest of the work. After final reassembly of the deck I ran another speed test, and what happened?

A nice average wow&flutter of 0.041% WRMS, only slowly rising with time. And this result was perfectly repeatable. So what happened?

Here is my theory: The Onkyo is not very service friendly. The mechanism has connectors on its control and supply cables, but the head cables are soldered or wirewrapped at both ends. Operating the mechanism outside of the deck is only possible by laying it on its back on a cushion of bubblewrap on top of the main board. I am assuming now that this horizontal orientation messed with the operation of the electromagnetic brake. Perhaps something in the reel hub produced excess stick-slip friction with rising temperature ...

Electronics

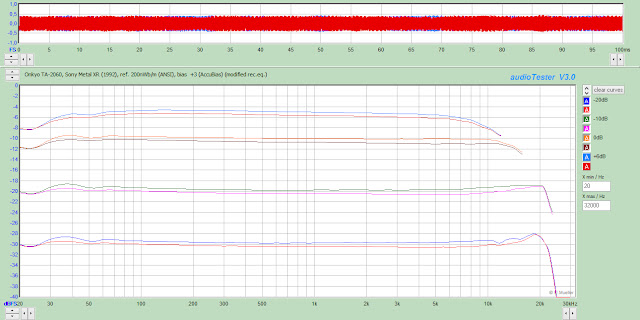

As you see these curves are remarkably flat and well-extended, with the little channel imbalance boding well for head health. At 0dB (Dolby level, 218nWb/m) the loss is 5 to 6dB at 10kHz. This is not bad at all, perhaps typical for the late 1970, but many later decks performed much better in this respect. It might well be that the designers were cavalier about treble saturation, after all they had ... Dolby HX.

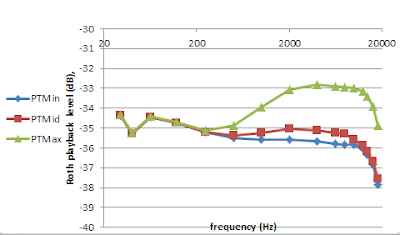

However, against the sublime -20dB rec/play frequency curves the playback-only response was disappointing (Hanspeter Roth 30Hz to 18kHz frequency burst cassette, after careful azimuth alignment):

A smoothly down-tilted response, levelling out above 6kHz. That 18kHz was reached without severe roll-off indicated fine alignment and no severe head wear. However, the total deviation being 4dB between bass and treble must be very audible. And indeed, playing prerecordeds or cassettes made on my Naks the high treble was present, but subdued, and the overall sonic picture was rather lethargic. I've said it before and will repeat it again: people keep on nagging about Nakamichi's presumed violation of the cassette replay standards (too much treble), but many other manufacturers did the same but in the opposite direction (too little treble), in a bid for artificially-enhanced signal-to-noise figures and brand lock-in.

With those admirably flat rec/play responses and a down-tilted playback response it has to follow that the record-response would be severely up-tilted. Recording white noise on the Onkyo and playing it back on the BX-300 confirmed this: blue/red Onkyo playback; green/pink Nakamichi playback.

Conclusion: the TA-2060 has by design a low compatibility with other machines and with commercially recorded cassettes.

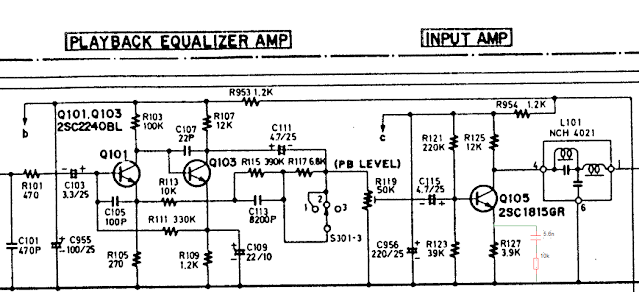

What is needed is an upward shelf in the playback chain, and a downward shelf in the recording chain. Luckily both proved very easy to implement. Contrary to most decks the Onkyo has an extra single-transistor gain stage between the replay amplifier and the Dolby decoder: Q105. Putting an RC network in its feedback tail provided the required treble-boosting shelf. A passive RC network in front of the recording amplifier did almost exactly the opposite, netting again a flat response. Both networks use the same component values, 5n6 and 10k, but that is entirely a coincidence.

Not only does this make the deck more compatible, it also helps with its record frequency responses. Remember the relatively high loss due to treble saturation? The new record equaliser drives less treble onto the tape, thus there is less saturation. The deficit is made up in playback. Of course there is a price to pay: playback noise. More on that later.

The TA-2060 has one set of internal bias settings and record level settings, and no external record level adjust: some choices were to be made.

I set the internal alignment for Maxell SXII 1991. Maxell UR 1994, after adjustment with AccuBias, then was 0.3dB short in record sensitivity, a perfectly acceptable figure. Sony Metal XR 1992, however, required the fine bias control at its minimum and then showed a sensitivity of -1.4dB. Not so nice!

Relative to Dolby level MOL was +4.4dB and +3.5dB for type I and II, but a very poor +0.4dB for type IV. Clearly some more effort was needed to make metal tape work on this deck. Putting 1n8 in parallel to C255 boosts high treble during recording type IV. Compensating this with higher bias (+3 on the AccuBias knob) then yields a flat(tish) response and MOL at +2.6dB. Acceptable, though clearly still underbiased. Not much can be done about this: higher treble peaking in the record equaliser would call for more bias to compensate, and with the limited range of AccuBias this would move the bias window for types I and II away from their sweet spot.

You will remember from before that the unmodified deck's saturation performance limited treble extension on the 0dB and -10dB curves, with -3dB already being reached well below 10kHz. With the modified record and playback equalisers this improved significantly, as can be seen in the following frequency sweeps (top to bottom UR, Metal XR, SXII):

Finally it is time to have a look at Dolby HX. HX uses part of the Dolby B circuit (it cannot be operated on its own) for estimating the amount of treble in the incoming signal. This is then used to control a bias servo, alongside some dynamic equalisation. The aim is to reduce bias in the presence of strong music programme treble, thus avoiding saturation. Let's have a look at SXII with Dolby B, and then with Dolby B + HX (note that this is on the modified deck, already with improved saturation characteristics):

The Dolby B curves are remarkably flat, indicating excellent tracking. Adding Dolby HX then clearly extends the treble limits of the 0dB and -10dB curves, as intended, but also depresses treble by more than 1dB in a wide band starting from 4kHz, something unintended and audibly counterproductive. The same phenomenon was mentioned in High Fidelity magazine's review of the Harman Kardon HK-705 in August 1980. It is clear why Dolby Labs quickly abandoned the complex and costly HX in favour of Bang&Olufsen's HX Pro: it did not really work.

The output of the deck in play mode had some 50Hz/100Hz pollution in the left channel. Placing a thin shield of mu-metal between power transformer and tape mechanism knocked this down by 2dB or so, making both channels equal. Playing without cassette, or equally a bulk-erased BASF Chromdioxid II, had playback noise at -52.5dB and -58.8dB(A) relative to Dolby level. The no-cassette A-weighted result is 6dB worse than the Nakamichi BX-300. Moreover, the large difference between unweighted and weighted noise levels indicates the presence of more than average low-frequency garbage. This is not the quietest deck, and with the sub-optimal MOLs also not the most dynamic one. But let's not forget that it hails from 1981, when cassettes themselves were also much noisier than in the 1985-1994 period.

Sonically the TA-2060 is a bit lean, but it sounds detailed and clean in a friendly way, its character a bit like an LFD amplifier. As can be deduced from the low MOLs it does not like recording at high levels: +3dB really being the limit for type II, even less when the music is bass-heavy: 100Hz MOL is barely 0dB. The needle peak meters indicate pulses of 50ms duration or longer more or less correctly, but they under-read 10ms pulses by 3-4dB.